Brian Michael Bendis and Robert Kirkman may be well renown for their impressive writing chops across several genres, but they haven't reached the heights of diversity that Raoul Cauvin's done. He's mostly written short page gags of all sorts involving nurses (Les Femmes en Blanc), cops (Agent 212), cupids (Cupidon), gravediggers (Pierre Tombal), psychaitrists (Les Psy), photographers (Les Paparazzi), and schoolchildren (Cedric). In addition, he's also written longer stories, such as American bodyguards during prohibtion (Sammy), and before that, got his major start by writing about two soldiers during the Civil War (Les Tuniques Bleues).

The Bluecoats, (also known as The Blue Tunics) were created to deal with the loss of Lucky Luke who left Spirou magazine to join Pilote magazine, who produced comics such as Asterix and Achille Talon. While basing a humourous comic on the Civil War seems like a risky proposition (especially with all the bad blood it brings up), Cauvin doesn't restrict himself on whether the war is justified or not. Like M*A*S*H, the series takes the theme of war as a backdrop for historical context. It focuses on two men in the army; Sergeant Cornelius M. Chesterfield and Corporal Blutch.

Blutch wants nothing more than to get out of the army and find ways to desert with minimal risk to his life, while Chesterfield sees his war position as a noble figure capable of great missions. Despite their conflicting viewpoints, they manage to remain close friends who've saved the other's lives multiple times. Even though Blutch rebels against authority, he won't hesitate to fight for his men, and while Chesterfield is proud of his war wounds, he's unnaturally clumsy and shortsighted.

It's this conflict of interest that manages to make the Bluecoats more interesting than your typical jingoistic army story. In fact, European comics have more western cowboy comics than Americans. It's rather ironic that foreign comics do a better job of retelling American history than they could do on their home soil.

When Louis Salvérius, the main artist for the Bluecoats suddenly died after completing the sixth book, he was replaced with another artist, Willy Lambil. Since then, he's drawn all the Bluecoat albums to date. He must be doing something right, since it's reached its 53rd volume with no sign of slowing down.

With his grey hair and mustache, Raoul Cauvin is like a French version of Stan Lee, only without the shameless huckerism the Marvel spokesman is well known for. And unlike Stan, Cauvin respects his artists and is able to back up his claims. He's recently made several cameos in his latest comics, but considering the man's output for over 40 years, it's well deserved.

But enough about the man behind the comic, how about the comic itself? Well, it's drawn by the same artist who did the Bluecoat series. Careful readers will recognize that Lampil's name is an obvious pseudonym for Willy Lambil. Strangely enough, while the main cartoon artist and writer's names are thinly veiled caricatures, the other cartoonists are referred to by name without hiding their identities.

My lack of knowledge of French artists probably reduces my ability to appreciate this spread, but that shouldn't detour anyone else from trying. Most people don't know what their favorite artists look like either. The series is also slightly autobiographical in nature, as it shows the shaky relationship between artist and writer, as evidenced by the interior cover image:

While Lampil might harbor some resentment towards his partner, it doesn't stop him from remaining good friends with him. Blutch and Chesterfield manage to remain on good terms despite having different ranks and conflict of interests.

The offending line while watching the Bugs Bunny cartoon was "Why can't you write something as funny as that?" Lampil's wife is saying something along the lines of, "We had a lovely time!"

For the most part, Lampil is prone to bouts of exasperation and depression. Despite being in a profession that most people think is fun, a lot of the cartooning process is hard work. Not to mention that for the most part, even in a country that respects the ninth art, there are some artists who are better admired than others. Below is a situation that any artist at a comic convention can easily identify with. Lampil is paired up with another artist at a bookstore to do signings for anyone who's interested in their latest album. In addition, the manager's done the courtesy of surrounding them with various flowers to make their table more attractive. So the two of them sit and wait... and wait... watching the various people go by, hardly casting them a glance... when one customer catches their eye.

"How much for that plant?"

"Excuse me?"

Once the florist's sold everything there is to offer, he asks the cartoonists if he wouldn't mind signing one of their albums for him? We don't get to see what they drew, but they obviously got their little revenge, since the clerks say there's no way they could show the books to their children.

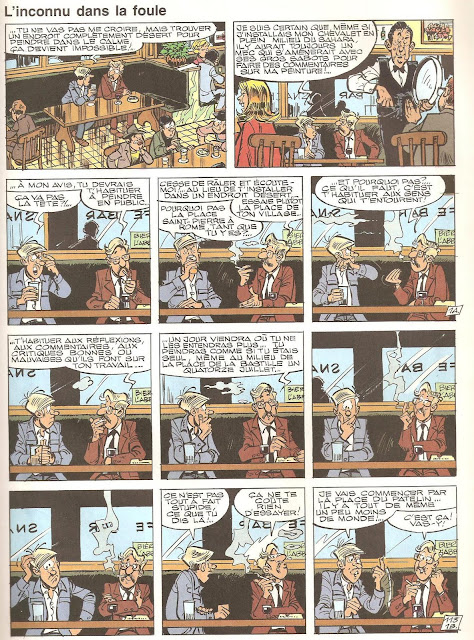

In another example, Lampil wants nothing more than to paint in peace and quiet. Privacy that he gets none of, since everybody and their mother wants to give their comments about what he's doing wrong. Getting critical feedback with somebody over your shoulder is not the most productive creative process as any artist can tell you.

So, after making his complaints known and explaining his problem to Cauvin, he proposes an unique solution:

"Why don't you go paint in public?"

"Are you off your head? Why would I want to do that?"

"Why not? If you're going to be interrupted while trying to paint in private, then you should get some thick skin in the middle of a crowd of people. That way, you can tune out their comments and be able to work even in a war zone."

"Actually, that's not a bad idea!"

"What do you have to lose?"

"Allright then, I'll start painting for the world to see!"

"That's the spirit!"

So Lampil hesitantly goes out into town and plunks himself right into the busiest intersection...

And nobody bats an eye, thereby defeating the whole point of the exercise.

It doesn't only focus on Lampil, as we sometimes see things from the author's point of view. As it's well known, our writing process is greatly influenced by what happens to us in our day-to-day life.

"What're you up to?"

"Thinking up the next Bluecoats script!"

"So! What're we gonna do now?"

"Quiet! I'm thinking!"

"Yesss? Oh, helo Mr. Lampil! Yes, yes, he's here... / Dear! It's for you!"

"Yeah, hello?!"

"When are you going to get the script ready? I want to tackle the storyboards!"

"I was in the process of outlining the story when some idiot derailed my train of thought..."

"Oh, okay! I got it!"

"Hey! What am I doing here?"

An hour later, the cast has grown to include dozens of characters in search of a plot that has yet to reveal itself.

In addition, it's short - only seven volumes long. The references to the Bluecoats might be problematic, since they're not as well known as other European icons such as Asterix, Tintin, the Smurfs and Lucky Luke. Hopefully, if Cinebooks gets more successful with their comics line than other companies, we could see Lampil in the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment